How To Draw With Rhythms - The Definitive Guide (2026)

Rythms are an advanced drawing skill, that can take your drawings to the next level.

They are present in everything you see, and once you become aware of them, you can use them to improve your images.

In this guide you’ll learn what rhythms are, why you should care about them (if you want to draw better), and how to improve your sensitivity to visual rhythms using targeted exercises.

Let’s get into it!

What are rhythms in drawing?

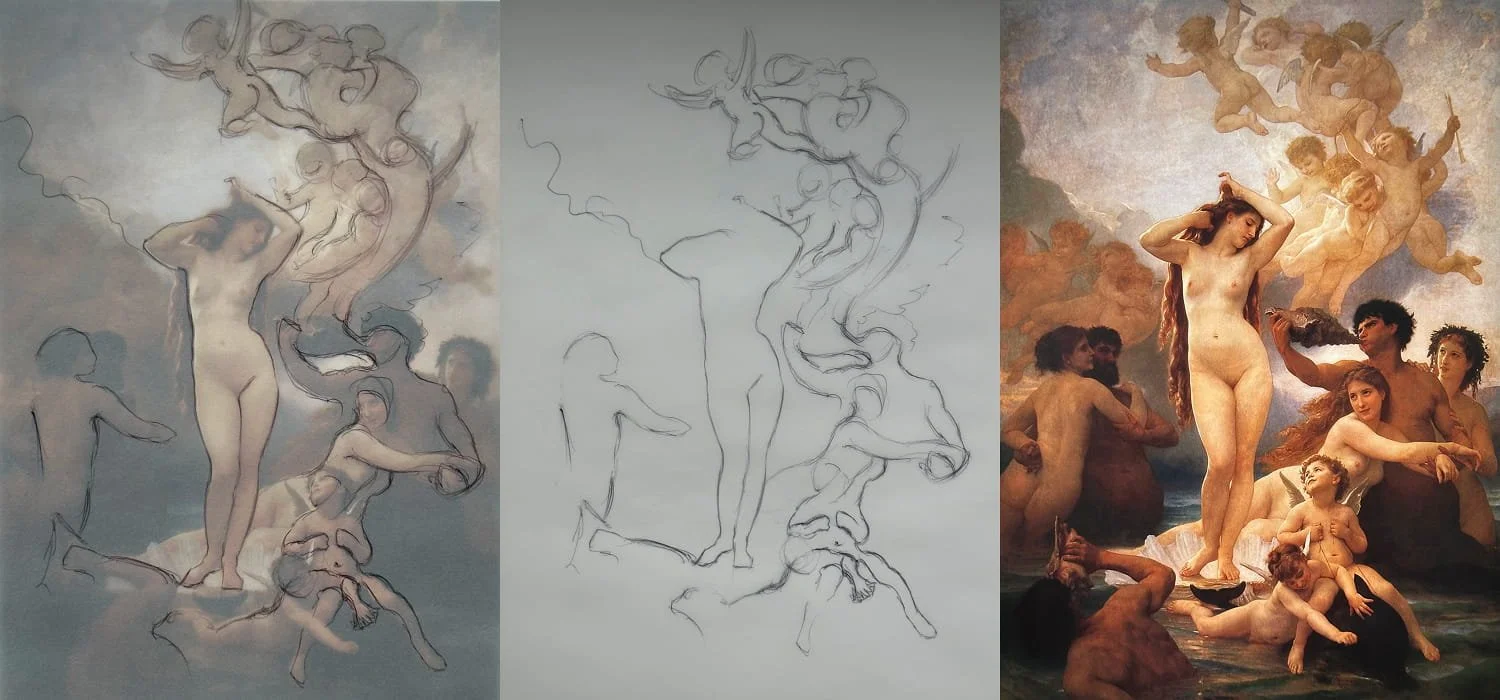

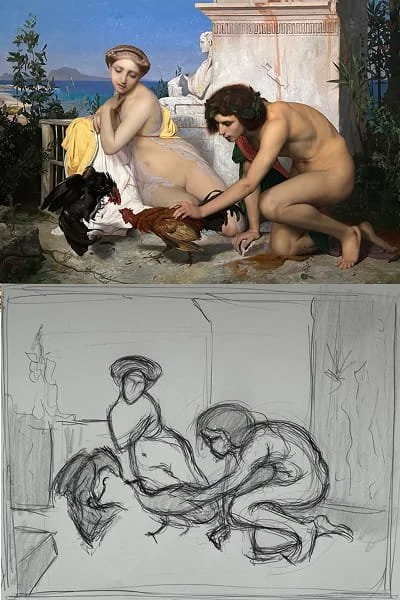

Masterful display of rhythms by Bouguereau.

Rythms are invisible lines that make everything in your drawing connect. Rhythms create unity. And if everything in your drawing connects, and climaxes into one focal point, then your drawing gains pictorial power.

Take a look at the painting above by William Adolphe Bouguereau.

Notice how long, fluid S-curve rhythms are woven into the picture, connecting every tiny movement, and channeling all parts of it into one unified expression through the focal point of the image: The female figure in the centre.

More specifically, Bougereau designed the picture such that the silhouette, or contour of the female figure is of special interest, and all rhythms in the background flow in harmony with that contour.

That’s the power of rhythm.

Rhythms in drawing are like rhythms in music.

They operate in the background and might not be obvious to your perception, or as easily noticed as the melody of a song, but without rhythm the whole piece falls apart.

Many painters have made analogies between painting and music, and it might help you to think of rhythms in your drawings like rhythms in a musical song.

It’s an emotional pattern, expressing itself visually.

Why you should learn how to use rhythms in your drawings.

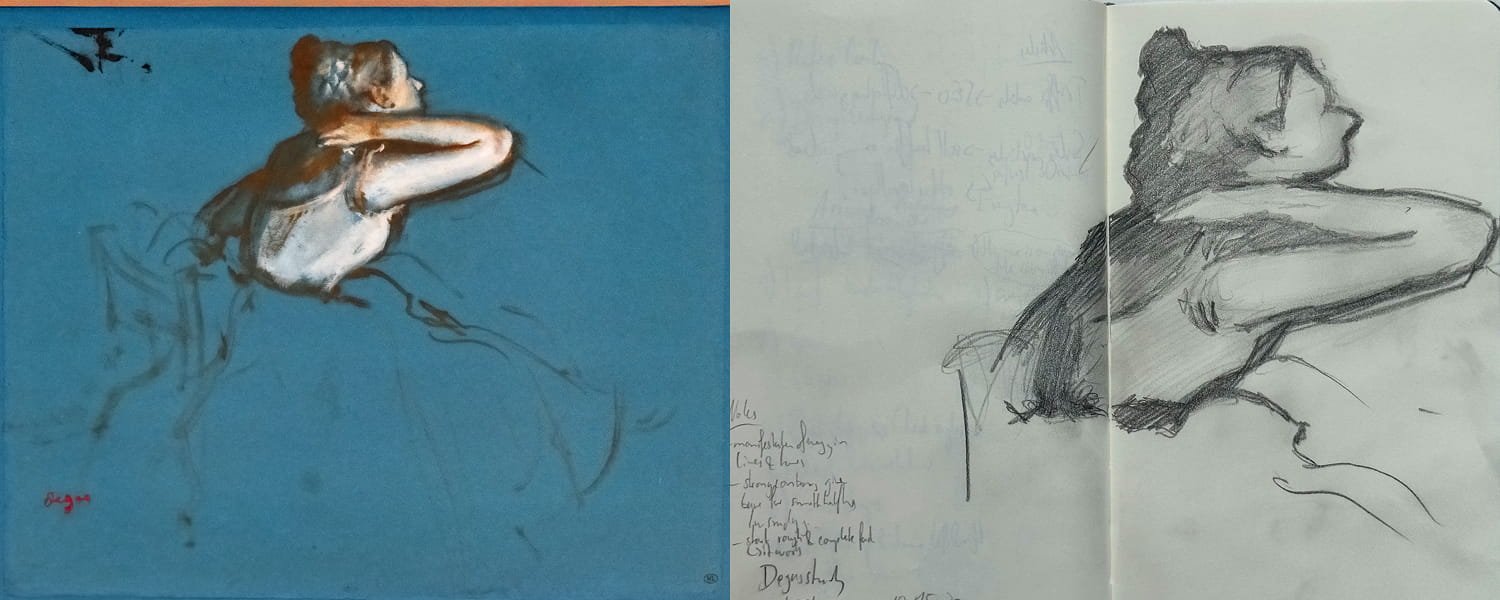

Rhythm study of Edgar Degas.

If your drawings lack connectedness and feel disjointed

If you want to increase the emotional impact of your drawings

If you want to make your drawings “feel” more realistic, instead of just “looking” realistic

If you are chasing that professional look where everything seems to “come together”

If you want to access a deeper level to drawing that’s much more fun…

Then you should read the next section on how you can add rhythms to your drawing skillset.

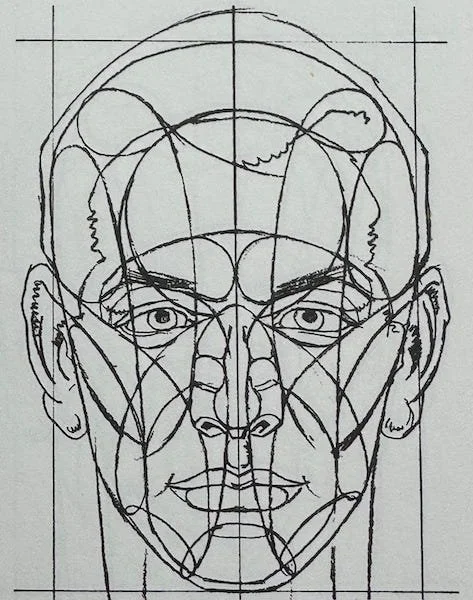

A note on Reilly rhythms.

An example of Reilly rhythms as taught by Jack Faragasso.

There is a famous teacher called Frank Reilly who came up with some essential rhythms for drawing the figure and portrait.

He created a diagram to teach those rhythms to his students.

Personally, I found reilly rhythms helpful only in the beginning, when the concept was completely new to me.

Shortly after, I got the most out of studying the greatest painters in history, and how they used rhythm in their paintings.

You’ll find that there are almost no rules, yet many rhythms do re-occur in the figure and portrait.

Rhythms tend to follow anatomical landmarks, muscles and bones, for which the Reilly diagrams are helpful, but not only. As you saw in the Bouguereau painting, some rhythms are like invisible lines connecting parts you wouldn’t even guess are connected at first glance.

Think of rhythms as a design tool.

Beyond Reilly - The rhythms of the masters

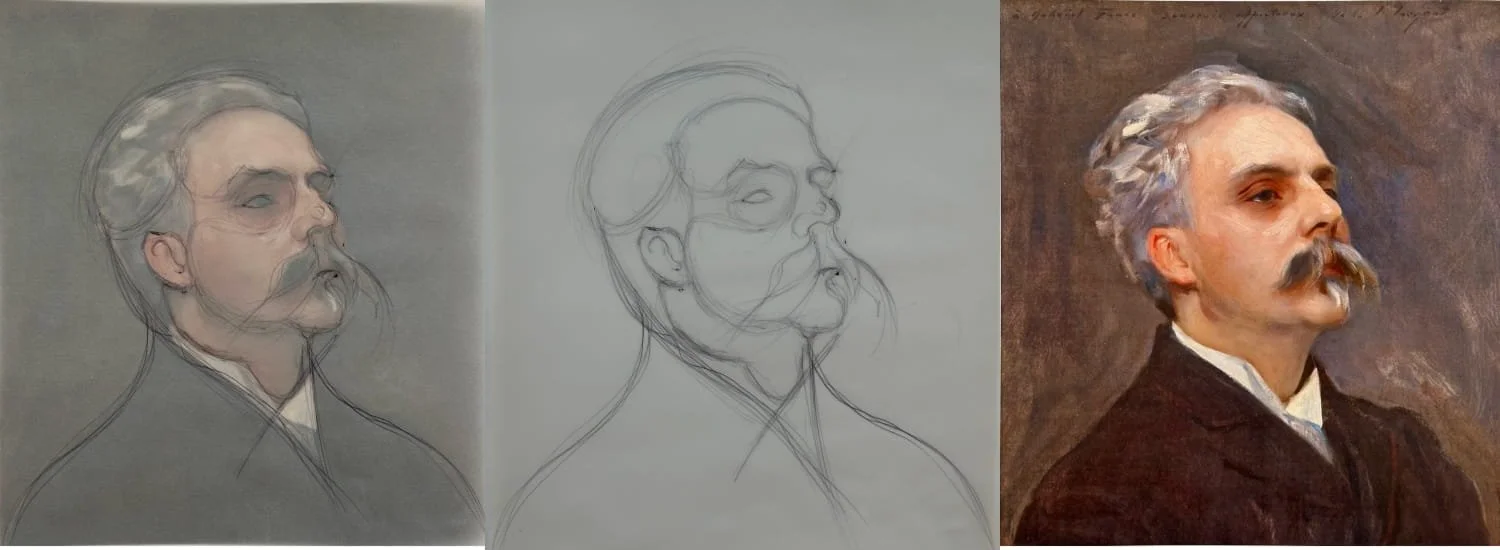

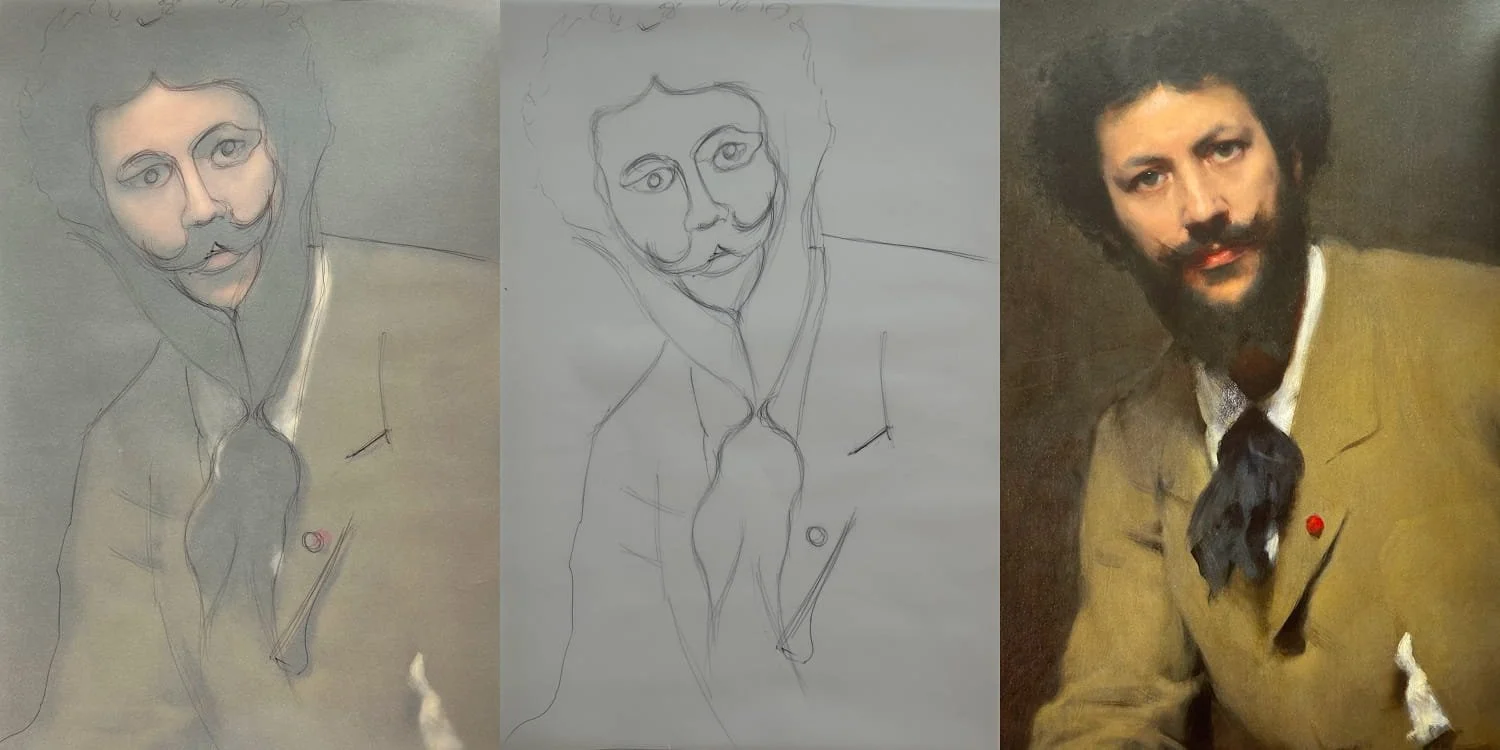

Rhythm study of Sargent portrait. Notice the circular nature of the rhythms around the skull.

Here’s the thing: Every drawing you make will present it’s own unique rhythms.

Yes, you can apply the Reilly rhythms if you want, but the next level is becoming aware of the rhythms that are unique to your picture.

Notice how in the portrait above by Singer Sargent, like in the Bouguereau painting, everything connects. His brush strokes make you flow from the forehead down the noise, through the beard and back up through the circular rhythms of the skull.

His rhythms are a visual design.

How to draw with rhythms step-by-step.

Just like any skill in drawing, it’s best to use exercises that isolate the skill you want to get better at.

Once you can apply the skill in a controlled, isolated environment, you can start using it in unison with your other skills while executing a drawing.

Here are three exercises that help you see, execute and feel rhythms on a deeper level.

Exercise 1: Tracing rhythms

In this Sargent portrait, the rhythms seem to flow down the picture.

For this exercise you need tracing paper and a master painting you like. You can also do this in a painting app, or draw freehand from a master reference.

Simply trace the linear rhythms you see, and try to keep all of them connected. I suggest you “enter” the painting at the main rhythm that sticks out to you, and from there try to find a path through the image without breaking the rhythm for as long as possible.

In the painting by Sargent above you can see the face flows in a triangular shape down the image, and connects seamlessly to his tie. The beard and the shapes of the eye also follow this rhythm.

This exercise is a lot of fun, as it unveils the mystery behind every painting. It’s like solving a riddle.

If you don’t have tracing paper, you can also study rhythms freehand.

Fast free-hand rhythm study of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting “Battre des Coqs”.

While your accuracy might not be as perfect in a free-hand study, you’ll find that even if the measurements are somewhat off, if the rhythms connect, your study will feel unified.

Of course you can take your time to get high degrees of accuracy while doing these studies, but even quick short studies can be very insightful.

Exercise 2: The “searching” hand

Take a look at this masterful painting demonstration by Daniel Greene by clicking here.

Take a second to watch his hand move, before making a mark on the canvas.

What you’ll notice is that his hand hovers over the the canvas before making a mark, searching for how his hand fits into the rhythm structure of the painting. Then, once he practiced the mark he wants to make and feels how it connects to everything else, he makes the mark in one stroke.

In your next drawing, try this approach:

Make your hand “connect” to the drawing, by following it’s rhythms before making a mark.

Practice the mark you want to make, in air, above the drawing, before making it in one confident stroke.

By adapting this mark making habit, you’ll find that your marks will become much more rhythmical and accurate at the same time.

Exercise 3: Word descriptions

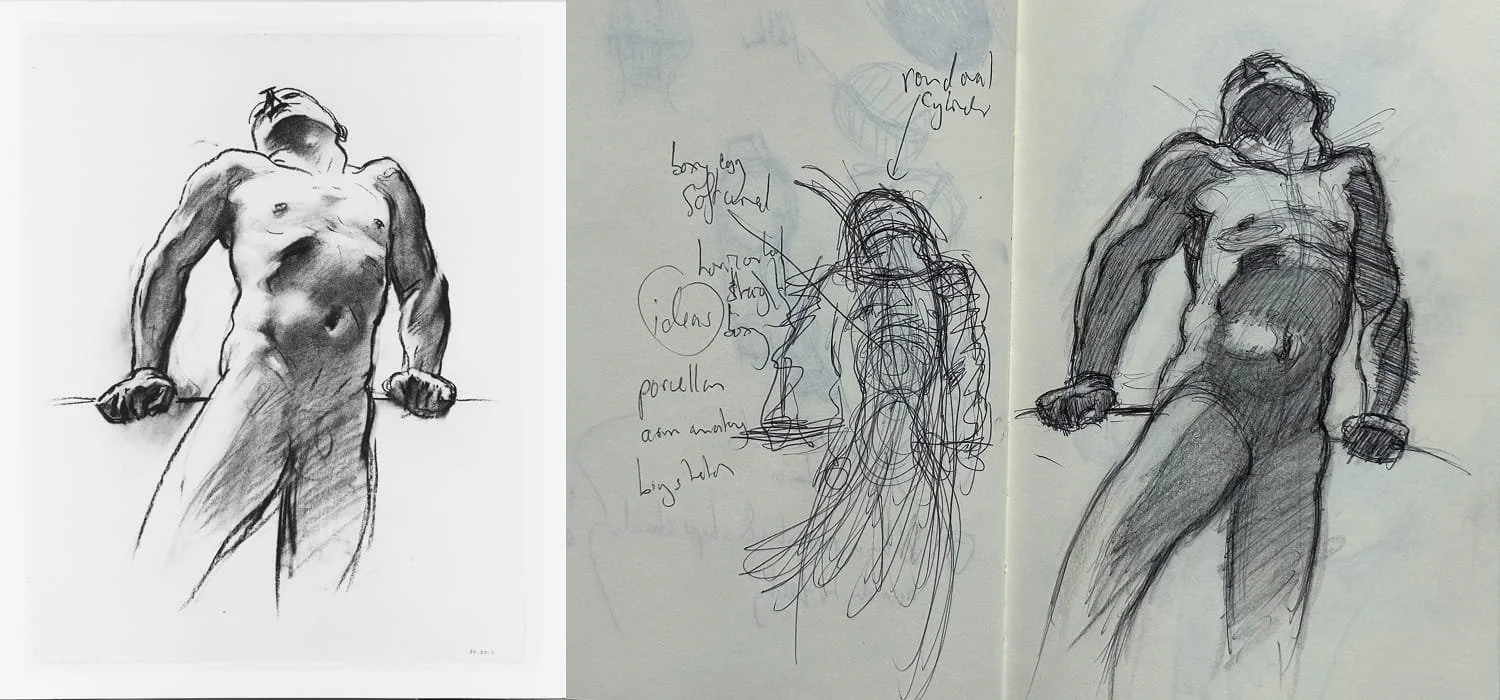

Quick rhythm study of a Sargent drawing.

Drawing exercises many different faculties. So far you learned an exercise to train your ability to see rhythm, and also an exercise to get your hand sensitive towards rhythm.

Using your conceptual faculties to make sense of visual patterns and translating them into emotions and associations can also be very helpful.

It’s something I’ve first learned from my teacher Chris Legaspi, who recommends writing down words you associate with the reference before drawing it, to get in tune with your emotional reaction. This practice is equally helpful for studying rhythms.

Simply pick a master painting, and write down some associations you have with how it feels.

In the study above associations that came up for me were:

Theres a strong zig-zaggy rhythm thorugh the arms where all the weight of the torso rests. The arms feel locked in place.

There’s a long fluid rhythm line trough the torso. The torso feels fluid and stretched.

The more you put words to what you see, the more nuanced your sensitivity to rhythm becomes, and the more natural it will feel to use it in your drawings.

What’s the difference between rhythm, gesture and linear composition?

A lot of these terms are not as perfectly defined as let’s say a concept in physics.

Here is how I think about it:

In any drawing or painting, how all the pieces connect to each other matters A LOT for the impact of the image.

How they connect to me is a rhythm.

These connections can feel long fluid and flowing. They can also feel erratic, zig zaggy, or really any other emotion you can feel. There’s limitless possibility.

When you look at rhythms on a macro scale, meaning at the image as a whole, you are thinking in terms of linear composition. To me linear composition is about designing the macro rhythms of the image, and how things flow.

Gesture to me is the rhythm of the figure. That’s usually how we practice it. We look at a figure in relation to its movement and situation, and try to figure out its rhythm.

Here’s why I still suggest you think of rhythm as it’s own concept (not just gesture or linear composition): Rhythms flow not just on the macro level, or in the figure, they have to be part of every single mark you make in a drawing, down into the finest detail.

If you watch a master painting, you’ll notice that every little detail, every mark, every brush stroke, connects to the rest of the painting.

Closing thoughts

That’s it!

I hope you found this article useful.

If you apply what you learned you’ll be surprised how fast your drawings improve. Within a few days and weeks you’ll start to draw “on the beat”.

And your drawings will have greater emotional impact…

If you liked this article and crave a structured learning experience, check out Foundations of Realism below.

Until next time!

Felix